By Aiden Carrera

Fall 2023

Oklahoma State University boasts one of America’s coolest-looking campuses. Amidst the stunning architecture and red-bricked roads lies a playground for unique and passionate skateboarders to ride around. OSU’s campus is full of geometry perfect for skateboarding, and plenty of long and flat areas to cruise around. The skating subculture is thus a prominent one, and this vibrant community defies stereotypes and brings a unique dimension to the university experience. Although skateboarding is not a traditional academic pursuit and minimal scholarly research is available, its presence at OSU is undeniable. Beyond that, skateboarding around OSU is not just a recreational pastime but one that brings personal growth, and artistic expression, and ultimately brings people together. This paper will delve into the history of skateboarding as well as use surveys to gather data from the public. Additionally, this paper aims to uncover the differences between skateboarding culture at OSU and the broader skate culture found across the nation, shedding light on the causes of these divergences.

Before we get into the nitty gritty of OSU’s skateboard culture, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the historical context and evolution of skateboarding in America. Skateboarding holds a widely popular reach within American society, but it has faced numerous waves of popularity. The roots date back to the 1950s when kids searched for a cheap way to ride on their own set of wheels. The options included wagons, scooters, and roller skates, which led to a creative few taking the wheels of roller skates and attaching them to a 2×4 (SurferToday). From there, growing commercial interest made skateboarding a concept, and eventually, the first Roller Derby Skateboards appeared on store shelves in 1959 (Skate Deluxe). Surfers began to take interest in these boards often because surfers wanted a way to transfer the feeling of waves to the streets and rode on days when the waves were lacking (SurferToday). From there sport gained momentum, particularly on the coasts, and more and more companies began investing in the industry. Shortly after this boom, the wheels started falling off – literally. Not quite literally, but the poor-quality wheels didn’t grip the road well and caused some nasty falls, which led to the ban of skateboards within numerous cities (SurferToday). But fear not, by 1972 Frank Nasworthy’s urethane wheels and better manufacturers got the industry rolling again (Skate Deluxe). This boom brought millions of enthusiasts, as well as innovations such as the precision-bearing wheel (SurferToday). Skaters also started getting featured in magazines which brought more popularity to the sport (Foley 4). Freestyle skating, a form of flat ground skating in which music is often played to a routine, also became increasingly popular (SurferToday). Additionally, skateparks also began popping up, and skaters went from skating on the streets to getting air using ramps and empty pools (SurferToday). Eventually, in 1978, Alan Gelfand dropped the ollie, which became the foundation for nearly every other trick on a skateboard (Lancaster). The ollie is a way for the board to essentially jump with the rider, involving the back foot hitting the tail of the board on the ground and the front foot leveling the board out. After the ollie, Rodney Mullen created the notorious kickflip, in which the board flips 360 degrees under the rider (Lancaster). With these innovations, many new flip tricks were created by skaters, including Rodney Mullen who was known as the “godfather of skateboarding tricks”, and many took these tricks to the streets (Lancaster). With street skating, the skate culture began to mesh with punk and new-wave music (SurferToday). Additionally, with the Thrasher Magazine and later the Transworld Skateboarding Magazine, the scene started growing a more unique identity (Skate Deluxe). With film technology such as the VHS, videography became a vital component of the culture (Skate Deluxe). Videos allowed new tricks and riders to become discovered and made it possible to become a professional skateboarder. By the late 1980s, skateboarders’ fashion also contributed to the culture, with shoes becoming more important. Shoes such as Vans and Converse became hugely popular and big sellers (SurferToday). However, after some questionable corporation drama and an oversaturation of contests, skateboarding suffered another crash (Foley 4). This one saw massive leaps in insurance costs and fewer skateparks built (Foley 4). Skateboarding went underground for a while, and cop intervention reached its highest. Eventually, the skating scene slowly built itself up again until the mid-1990s. With the popularization of cable tv, X games became a big hit (SurferToday). Later, in 1999, Tony Hawk, at X Games in San Francisco, became the first to land the 900 (Foley 5). The 900 involves two and a half body rotations on a standard vert ramp. The trick brought a new post-Tony Hawk era to skateboarding. The Tony Hawk Pro Skater video games brought even more people to skateboarding. Additionally, with the increasingly popular use of the internet, video parts became even more common and could be shared worldwide. Over the years, skateparks have increased and now sit at about 3,500 parks in the United States alone, with 651 being funded by the Skatepark Foundation, formerly the Tony Hawk Foundation (The Skatepark Project).

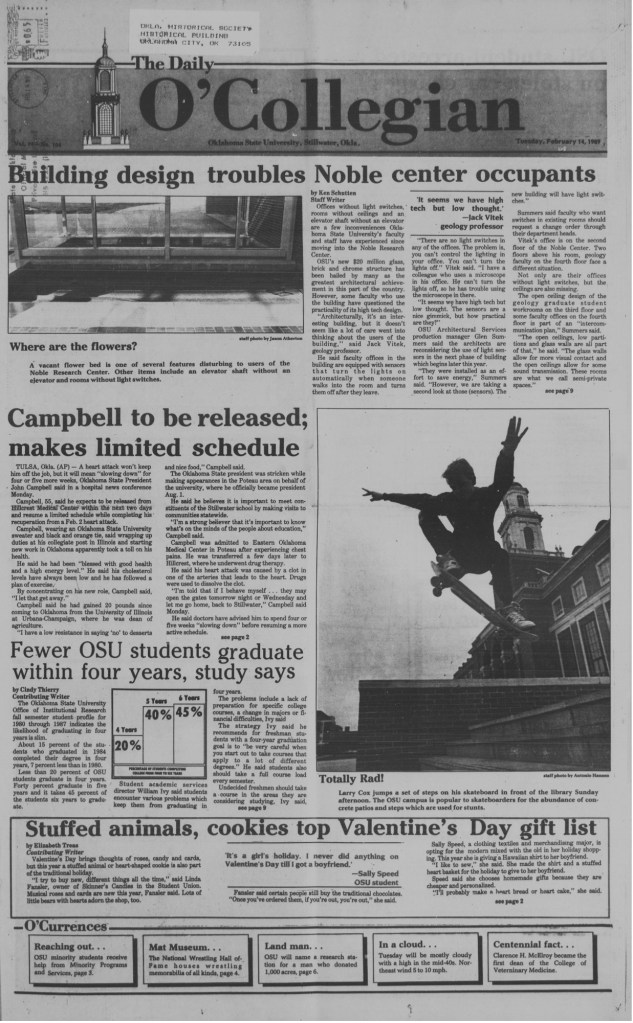

Now that the history lesson is out of the way, it’s important to know about skate culture in the U.S. as it is now. Skateboarding might seem like a rebellious, counter-culture thing, but it’s really a diverse community full of passionate and creative skaters. With approximately 8.75 million skaters as of 2021, the community spans many different demographics (Statista). A survey conducted in 2019 found that the majority of skaters identified as “male (75%), straight (72%), and White (54%)” (Corwin 7). Out of the remaining-colored skaters, 36% were Latinx, 33% were multiracial, 10% were of African descent, and 11% were Asian (Corwin 7). When asked on a scale of 1-5 how responders feel their gender or race affects them, most skaters felt very slightly less affected when faced with a skater vs a non-skater (Corwin 19). Within this survey, respondents reported that they skated about 4.2 days a week (Corwin 8). Of these days, about 50% skated in the streets, while 36% skated in parks, vert ramps, and transitions (Corwin 8). Transition is skating focused on half pipes, mini ramps, and bowls often involving using your body for tricks. The next question involved why the skateboarder skateboards. For many, it’s more than a hobby and is like a therapy session on wheels. The top answers were having fun, managing stress, learning tricks, being creative, expressing oneself, and making friends (Corwin 12). A lower number responded they skateboard for transportation, which is an important factor to note. When asked what they like best about skateparks, only 14% responded that they had never been, while most responded that they like to meet friends, and the people there (Corwin 14). These questions help build a picture of the average skater. Additionally, when it comes to rules, the regulations in America are loose. In fact, searching the term “skateboard” within Stillwater Oklahoma’s codes and ordinances, zero results show up (Municode Library). Although there aren’t many universal laws, it’s often the case that a skateboarder is considered a pedestrian (Safety First). This means that skaters are free to ride on public sidewalks but are not permitted on streets (Safety First). They also aren’t allowed to skate on private property without the owner’s permission and should follow right-of-way as well as yield to stop signs and lights (Safety First). Because of these looser rules and the prevalence of skate parks, skaters often don’t break any rules. On the other hand, some hardcore skaters will break into private properties to get clips on generally unavailable geometry. When it comes to OSU’s skate culture, we can briefly peek into the past to see if there’s any resemblance to the vibe of general skate culture’s past. Unfortunately, looking through past news, articles, and records, there are limited resources. One gem from the past is the newspaper of the OSU’s Daily O’Collegian which shows on the front cover college skateboarder Larry Cox pulling off a gnarly ollie down at least a 5 stair in front of the Edmond Low Library (O’Collegian).

The title is “Totally Rad!” and the caption states, “The OSU campus is popular to skateboarders for the abundance of concrete steps which are used for stunts.” This snapshot from ’88 shows that skateboarders were prevalent around campus and were already shredding on the architecture. It’s cool to see the skate scene at OSU has deep roots, especially considering it was the era of street skating. Moving on to the present, regulations and restrictions play a significant part in shaping a college’s skating culture. Like many other college campuses, OSU has a big, long rulebook of policies over skateboarding that permit or deny certain actions. The two main sources for this information are the OSU’s parking rules and regulations, and campus recreational policies. Within the parking regulations, the bulk of the rules are declared. These rules declare that skateboards are prohibited in garages including their steps or ramps (OSU 26). Skateboards are also prohibited on or in any university building, structure, stairway, sub-walk, elevated sidewalk, access ramp, step, retaining wall, handrail, or any other architectural element (OSU 65). On or in any planting area, grass area, or seeded area (OSU 65). On streets open for vehicular traffic (OSU 65). Where prohibited by sign or by OSU Parking or OSU police officer (OSU 65). In the immediate area of the Edmon Low Library, including the library mall and fountain area (OSU 65). These rules are tucked away on two separate websites and are relatively hard to find. This leaves skaters generally uninformed about them. Notably, the rule prohibiting skating around the Edmon Low Library indicates that Larry in the Daily O’Collegian was breaking a rule. This may be due to the lack of awareness of the rule or the date that the rule went into effect. Upon evaluating these rules, they are slightly harsher than those found in cities such as the rule preventing skateboards within any university building. This rule has been broken plenty of times with skaters bringing their boards to class or even just their dorm. Because it is often the case that these rules are not strictly adhered to, it might be expected that skaters are stopped often at OSU. Within an interview with one skater, I was told that police interaction is minimal, and that “they do not care at all”. This minimizes the rebellious skating culture at OSU and creates a more stress-free environment for skaters to ride in.

When comparing the skate culture at OSU and general skate culture, I created a survey that encapsulated many of the questions asked by the survey examined previously to see how OSU skaters compared as well as new ones to investigate further. For this survey, I created a Google Docs form and reached out to skaters in the OSU 2027 as well as the 2026 graduate Snapchat group chats to retrieve data. It’s important to note that of the 53 participants, most were OSU freshmen or sophomores. The questions that the surveys shared will be covered first. Similarly, to general skating, 73% of the survey respondents were male and 57% were white. Of the remaining respondents of color, 43% were Latinx, 17% Black or African American, 4% Asian, and 34% Native American. When it comes to how often skaters skated in a typical week, the average was 3.1 days per week. For why the skaters primarily skated, the number one answer was transportation at 40%, followed by recreation at 23%. The remaining answers were stress relief 13%, socializing with friends 7%, and creative expression 5%. The remaining answers were all of the above, which unfortunately was not a choice. When asked if they felt that their race affected how they were treated by other skaters, 92.7 % answered no, 3.6% yes, and 3.6% unsure. Of the yes answers, one of the respondents was Native American and another was Black. When asked if they felt that their gender affected how they were treated by other skaters, 78% answered no, and 16% answered yes, with 6% unsure. Of the yes responses 6 were female and 2 were non-binary. These cases are important to note and show that OSU skateboarding unfortunately has skaters that may condemn others based on gender or race. When asked if skaters had visited the local skate park, 16% answered yes often, 18% yes but rarely, 31% no, and a whopping 34.5% didn’t know it existed. When asked if skaters feel that there is a sense of community among skaters at OSU it was a very mixed bag including 9% strongly agree, 27% agree, 38% neutral, 13% disagree, and 9.1% strongly disagree. This wide variety of answers likely indicates that the community is large and that varying reasons for skating, such as transportation as opposed to creative expression, create smaller but tighter groups of skaters.

Additionally, the generally infrequent use of the skate park supports this idea. When asked if skate culture at OSU is inclusive to individuals of all backgrounds and skill levels, the answers were 20% strongly agree, 27% agree, 30% neutral, 15% unsure, 4% disagree, and 6% strongly disagree. This is a generally more positive response in comparison and shows that skaters are welcoming towards newer skaters. Moving on to the questions that weren’t shared between the surveys, for primary skateboard type, 53% of skaters rode a standard skateboard followed by 35% on longboards. The remaining responders under 12% included many different boards such as electric skateboards, Onewheel, cruiser, and penny boards. When asked why skaters started skateboarding, there were a wide variety of answers including “The best skate game to be created. Skate 3,” “i hate walking,” “I like anything with wheels,” and “The community surrounding it. Having to sacrifice a lot of time and experience a lot of pain to be good at it.” When asked if there should be rules regarding skateboarding rules on campus, 6% answered more rules, 43.6% answered the current rules, and 51% answered fewer rules. Finally, when asked if they have been stopped or questioned by campus police, 18% said yes and 82% said no. These regulations help build the picture of what skateboarders on campus are like. It seems that there are too many diverse skaters to have one unified and definable culture, with the longboarders who just want to cruise on their days off, versus the daily skatepark goers who practice grinds and get massive air on ramps. However, there is still respect given towards newer skaters and overall rules are followed enough that campus police don’t often have to get involved.

Finally, when it comes to OSU’s skating culture, the perspective of students is another important factor for skaters. I created a second survey which was for the non-skater’s perspective of skating at OSU. The survey was another Google Doc and received 208 responses. Again, this was asked in the group chats so many of the respondents are freshmen and sophomores. When asked how they felt when encountering skateboarders on campus, 25.6% answered positive, 61.1% answered neutral, and 13% answered negative. When asked how they felt about skateboarders using public spaces on campus, 38.6% answered positive, 49.8% answered neutral, and 11.6% answered negative. When asked if there should be more or less rules on campus, 25% answered more, 60% current rules, and 15% less. When asked if they have ever felt unsafe or experienced concerns due to skateboarders, there were many answers including “About been ran over or hit multiple times, ”Yes, some of them have absolutely no regard for pedestrians, you don’t need a survey to see this,” “If you’re going to be going Mach 6 you have to yell like you’re going Mach 6 so I know you’re coming down the sidewalk. I know you can’t stop. But I can move.” And my personal favorite,

My freshman year, I witnessed a student on a skateboard attempt a kick-flip off of the library fountain. This attempt however failed, and like the fall of Icarus, resulted in a high-speed descent through the air, ending with collision into the ground. Whenever said student ate said concrete, he landed dangerously close to a group of passerby’s, posing a safety threat to said passerby’s. Luckily, nobody was injured (except the skater, but he got up and brushed himself off) however his actions could have resulted in someone else being injured.

This is another example of somewhat violating the no skateboarding around the library area rule and even ended up with some pedestrians getting hurt. Likely, this rule was already in place since this likely happened within the past 3 years. On the other hand, many responded positively when asked if they felt unsafe such as “Nah dawg 🫡🫡🫡🫡🫡🫡,” “No. Let people skate it looks cool,” and “Not with skaters but bikers and scooters yes.” Finally, in the ‘anything else you wanna share’ section, they responded “for clarification, more rules in the sense of more clarity with the rules in place,” “If a skateboarder’s coming up behind you, they should say something to you instead of almost running into you,” “if they can do kick flips then they’re allowed to ride anywhere cause that shits cool as hell,” “LET THEM SKATE BRO BFFR” and “I just wish they would slow down when riding through big crowds.” Within these entertaining answers was a common answer of speaking up when behind people and passing. Another common answer was to slow down when coming to blind corners. From this survey, there is a large amount of people who support skaters, but for those who don’t, skaters need to follow some simple etiquette. I believe that these people are in the right and skaters should be giving much more attention when around other people. The rules should not change but there should be a code of conduct of sorts for skaters to follow. This includes giving a pedestrian plenty of space when passing and slowing down at all blind corners as well as big crowds. Additionally, if a skater is newer, they should work on their turning, speed, and overall comfort on a board before riding to class or when there are a lot of people around. These small changes would be enough to help prevent accidents and ensure the safety of pedestrians and skaters.

Overall, the culture of skateboarding at OSU is a diverse community on campus and is more than just cruising and ollies. From the history captured in 1988 to the present-day longboarders on campus, OSU’s skate culture is at least prevalent enough to get one picture in the newspaper. Despite the variations in individual motivation, the survey results highlight a multifaceted culture. The mixed responses regarding a sense of community suggest that there are opportunities to unify. Additionally, OSU’s skate culture is shaped by slightly strict policies, but overall minimal enforcement which ends up fostering a peaceful environment for skaters. The general public’s perception of skaters reveals a range of attitudes which prompts some changes to be made. By embracing inclusivity, addressing concerns, and establishing a code of conduct, OSU’s skate culture can flourish and continue to thrive while giving the campus a unique and dynamic part of the university experience.

Works Cited

“History of Skateboarding.” Skate Deluxe, http://www.skatedeluxe.com/blog/en/wiki/skateboarding/history-of-skateboarding/.

“A brief history of skateboarding.” SurferToday, 2 May 2023, www.surfertoday.com/skateboarding/the-history-of-skateboarding.

Foley, Zane. “History of Skateboarding: Notable Events That Took Place.” Red Bull, 2 Sept. 2020, www.redbull.com/us-en/history-of-skateboarding.

Lancaster, Mark. “Who Invented the Kickflip? And the Origin of Other Skateboarding Tricks.” Pokatok, 19 Apr. 2023, pokatok.com/who-invented-the-kickflip-and-the-origin-of-other-skateboarding-tricks/.

“The Skatepark Project.” The Skatepark Project, skatepark.org/.

“Policies – Oklahoma State University.” Department Of Wellness, Oklahoma State University, 31 July 2019, wellness.okstate.edu/recreation/policies.html.

“Rules and Regulations.” Parking and Transportation Services, Oklahoma State University, 7 Aug. 2023, parking.okstate.edu/parking/parking-rules-and-reg.pdf.

“Daily O’Collegian, 1989-02-14.” Digital Collections OkState Library, Oklahoma State University, 14 Feb. 1989, dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/ocolly1980/id/15365/.

“Skateboarding participation in the U.S. 2010-2021.” Statista, Statista Research Department, 7 Nov. 2023, http://www.statista.com/statistics/191308/participants-in-skateboarding-in-the-us-since-2006/

Corwin, Zoë, et al. Beyond the Board: Findings from the Field. 2019, files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED609263.pdf.

“Skateboarding Rules & Skateboarding Laws.” Safety First – Skateboarding Safety, skateboardsafety.org/skateboarding-rules-and-laws/.

“Skateboarding Laws.” Findlaw, www.findlaw.com/traffic/traffic-tickets/skateboarding-laws.html.

“Municode Library.” Library.municode.com, library.municode.com/search?stateId=36&clientId=11688&searchText=skateboard&contentTypeId=CODES. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.