By Maylee Miles

Spring 2022

I was not trying to make history…I merely wanted an education

Nancy Randolph Davis (Waldrop)

As people come and go at Oklahoma State University, they might catch a glance here and there of a certain statue in the Human Sciences courtyard or wonder why there are several buildings with the same name. Unfortunately, looking at names and statues and wondering about them is likely as far as people will go when it comes to the legacy of Nancy Randolph Davis, and in all honesty, it is not far enough. Although it may not seem like it, the statue built and the buildings named in Davis’ honor are there for a very important reason, and they act as a reminder of the great struggle that she went through for this university to be as diverse as it is today. Nowadays, many people forget or don’t consider that there was once a time when African American people were not allowed to attend white universities or universities that were not designated for them, the same way that they weren’t allowed in white stores or white bathrooms. However, when taking a closer look, it is evident that the effects of these struggles are still around today, and even OSU continues with present-day reparations and cover-ups for their racist wrongdoings of the past.

In the era of Nancy Randolph Davis, the Jim Crow laws of the time were still very real and very serious. If a black man or woman was caught attending a college for white people only, they could be arrested. Any professors caught teaching those students could also lose their job, be fined, or be arrested for a misdemeanor in some states including Oklahoma (Pollard 423). To put this further into perspective, after Nancy graduated from Langston University with a bachelors in home economics, she enrolled at OSU in 1949 to get her masters in Arts in Home Economics, which was six years before Rosa Parks was arrested for sitting in the front of the bus in 1955 and before the civil rights movement was in full force. She had to endure the racism, segregation, and horrific laws against black people to fight for a spot in OSU to further her education. Without the risks that she took, OSU likely would have continued to be white only until the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1954, and probably still racist much further into the future when civil rights movements were taking effect. Although it is possible to find bits of Nancy Randolph Davis’ story here and there on the OSU website and get a basic understanding of her story, the true depth of her accomplishments and the things OSU did against African American people cannot be understood until the time period and in which she made her story is fully understood.

Looking back at the mid-1900s, it is easy to say that it was a time period of substantial pain for African Americans, but it was also an era of great accomplishment for them as well. The biggest threat that they faced at the time was the Jim Crow Laws. These laws were a collection of laws that legalized racial segregation and discrimination. They were “named after a black minstrel show character” and “the laws—which existed for about 100 years, from the post-Civil War era until 1968—were meant to marginalize African Americans by denying them the right to vote, hold jobs, get an education or other opportunities” (Onion). These laws were designed to ensure that African Americans were treated as less than human, placing those who were white (or passed as such) on a pedestal and destroying the lives of those who weren’t. Whether it was forcing black people to use a different, poor-quality restroom, eat meals far away from all the white people, or simply white people not getting punished for beating and killing black people, it forced innocent people into lives full of fear and despair for the way they were treated and forced to behave. In the 1940s, laws finally began to slowly be passed or changed to help African Americans a bit. In 1944, the Supreme Court finally “outlawed all-white primary elections” (Lynch), and this was one of the first actions that leaned towards change in the future. This was a big step for African Americans, but it still was a minuscule moment in the long fight for freedom. This same year in 1944 was the year that Davis enrolled in Langston University to pursue her Bachelor of Arts in Home Economics. After WWII ended in 1945, information got out that there were “repeated incidents of white brutality to black soldiers around southern military camps and the terrifying three-day riot of 1943” (Kellogg 9). This was not only violence done to soldiers fighting for their country, but violence to those who were supposed to be considered brothers and sisters in arms during the already brutal fight that was World War II. It took five years after these war incidents for President Harry S. Truman to order integration in the military in 1948. This was also the year of Nancy Randolph Davis’ graduation from Langston University (Pollard 420).

Although it was illegal for African American people to attend most universities at the time, Land Grant Universities like OSU had a different rule set because of a law known as the Second Morrill Act that was passed in 1890. This law “forbade racial discrimination in admissions policies for colleges receiving these federal funds. A state could escape this provision, however, if separate institutions were maintained and the funds divided in a “just,” but not necessarily equal, manner” (Earl). This meant that Oklahoma State University could continue to discriminate against black students and push them away from white students so long as they sent a little money to another separate “black-only” institution of their creation. Also, the separate institution did not by any means have to receive the same amount of money as OSU, it only had to receive a “just amount” which could be interpreted by the land grant universities in many ways. Of course, due to the racism and segregation standards of the time, OSU chose to create one of these “separate institutions,” and this became what we know as Langston University. At the time, “Langston offered no training in medicine, law, pharmacy, engineering, nursing, or any graduate program (Hubbell 1). Additionally, Langston was the only all-black college created in all of Oklahoma. This university served as a means to satisfy the black community in their desire for higher education while keeping them out of white-only universities and colleges. The separation in education continued for about 6 years after Nancy graduated from Langston until the ruling of “separate but equal” being unconstitutional in Brown v. the Board of Education in 1954. Unfortunately, even with this monumental court ruling, racism was still running deep within schools. In fact, shortly after the ruling there were riots all across the US from white people attempting to change the ruling.

One year later Rosa parks was arrested for her peaceful bus protest, and Martin Luther King Jr. began to rally mass amounts of people in his long fight for civil rights. Up until that point however, the civil rights fight was mostly done by a few brave individuals aiming for particular goals in their lives. Nancy Randolph Davis was one of these incredibly brave individuals who stood up alone not only for herself but for African Americans across Oklahoma who deserved access to higher education in ANY school.

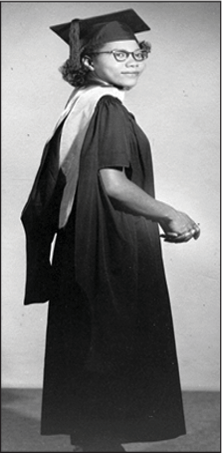

As aforementioned, Nancy Randolph Davis did end up graduating from OSU in 1952, but her journey to that point in her life was the opposite of easy. Randolph grew up in the age of the Great Depression as one of five children. According to the Nancy Randolph Davis video done by OSU in 2018, Randolph’s parents were “one generation away from slavery,” which meant that her grandparents were slaves. Her father worked on the railroad but lost his job fairly quickly because of the severe economic crash. Although there was government assistance at the time, her father chose not to apply for it. Instead, in order to keep the family afloat he farmed to supply them with food until he could get rehired. All the children had to help with the farming and housework as well as attend school and church. According to an interview done with Nancy Randolph, her parents always told the children to be “clean, neat, respectful, honest, and ALWAYS tell the truth” (Gill).

Despite the struggle in her childhood, Nancy Randolph was a near perfect student up until her last year of high school. Sadly, Randolph’s grades slipped her senior year because of the loss of her sister-in-law. Due to the loss, it became her responsibility to care for her four nephews, which was extremely hard for her (Pollard 417-18). On top of trying to finish high school, she had to essentially be a teen mom and take care of four children by herself, with a little help from her brother who was their father. All these hardships almost cost her a graduation, but she managed to complete her senior year and graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. She then went on to receive her bachelors from Langston and became a schoolteacher at an all-black school known as Dunjee Public High School in Choctaw, Oklahoma where she taught students how to build a better life for themselves for 20 years (“Nancy Randolph Davis-Oklahoma State University”). Even though she was a wonderful teacher in the eyes of her students and colleagues, teaching at an all-black school was not easy. Every school supply, book, and piece of furniture was second-hand, and funds were very limited. However, Nancy Randolph put everything she had into helping her students. Eventually, Randolph decided she wanted to further her education even more and chose to attend summer school at OSU for her masters of arts in home economics so that it would not interfere with her demanding job at Dunjee. With the help of family and friends as well as her own teaching money she had saved, she was able to stay in Stillwater and pay for her tuition. She was also able to live with a close friend from her hometown so that she did not have to commute from Choctaw to Stillwater.

Despite having everything she needed to attend the university, she was met with immediate discrimination upon requesting to enroll. “Upon her first encounter with the OSU dean of home economics, Davis received an unexpected rebuff. The dean told her that Negroes were pushing too hard; she suggested that Davis should go to Kansas, Colorado, or some other state where she would be accepted” (Pollard). Because of the treatment she received from the dean when she tried to enroll on her own, she had to enlist the help of OKC civil rights leader Roscoe Dunjee and NAACP lawyer Amos T. Hall to negotiate with the dean. Apparently that meeting was very secretive, and not even Randolph herself was told the details of the meeting despite it being her idea to enlist these people to help her. However, this meeting did eventually get the dean to grant her enrollment at OSU. Even with the excitement of finally getting enrolled as the first black student at OSU, this was not the end of her struggles.

In the beginning of her time at OSU, Randolph was not allowed to enter the actual classrooms due to Jim crow laws, and instead had to sit outside in the hallways in a nook. She spent a lot of time at OSU alone in those hallways looking in on other students receiving the same level of education she desperately wanted and deserved. Thankfully, with constant pressure from other students who were upset at the unfair treatment of a fellow student, teachers allowed Randolph to enter the classroom as long as other students constantly watched for any administrators that would cause trouble. Her classmates would also offer her transportation and help her study when she needed it which gave Nancy Randolph a little more security in her place at OSU (Pollard 422-23). Eventually, after a lot of hard work, Randolph was able to receive her masters degree in home economics in 1952, which was an incredible and monumental step towards equality in school systems in Oklahoma. Even with this achievement, OSU still had a ways to go before it corrected its racist history.

To this day, Oklahoma State University is still recovering from its deep history of racial segregation and discrimination. Even with the help of Davis and various laws to change how black students are treated, OSU is still a predominantly white institution, and it is still uncovering and changing wrongs that exist on the current campus and attempting to bury what happened in the past in order to move forward. The Second Morrill Act is still in effect, which means that OSU still supplies funds to Langston University just as it did in the mid 1900s when black students were forced to go there for higher education. That university is also still a very predominantly black institution with a 70% enrollment rate of African American students according to Langston’s official school website. OSU also named its English department building Morrill Hall which is to acknowledge the Second Morrill Act and the man who created the act Justin Morrill.

Recently, in 2020, OSU president Burns Hargis addressed the OSU A&M Board of Regents in changing the name of Murray hall and North Murray Hall, named after Oklahoma’s ninth governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray. In this address the president wrote “My request is based on the history cited by many on our campus that the building’s namesake, Oklahoma’s ninth Governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, had a record of advocacy for racist policies including segregation and the promotion of Jim Crow laws, which in effect stripped many Black Oklahomans of their constitutional right to vote. For many on our campus, the building’s name has invoked reminders of this painful history. Oklahoma State is committed to eliminating systemic racism and embracing our responsibility as a university to support solutions to the inequality and injustice our country and community faces” (OSU Regents). Thankfully the board agreed to remove the name from the building permanently. Murray Hall is also closed currently in 2022. Not only is OSU working on erasing its wrongs, but it is also working on reparations for them. Davis was named a distinguished alumni by OSU in 1999 and the university now offers 3 scholarships in her name and celebrates “Nancy Randolph Davis Day” each February. She got inducted into the OSU’s Greek Hall of Fame in 2012, and posthumously inducted to the OSU Hall of Fame in 2018. She also had a residence hall built in her honor in 2001 named Davis Hall (Waldrop).

In summary, the journey of Nancy Randolph Davis and OSU was a tumultuous one, linked by the will for equality in education. Fighting for equality alone through times where it most definitely could have gotten her hurt or killed, Nancy marched her way steadfastly into a new era for higher education. Because of her sacrifices and willingness to stand up for herself and black students across America when no one else would, Nancy Randolph serves as an inspiration to everyone to pursue dreams and goals, and to stand up for themselves even when it feels like the whole world is against you. Her accomplishments earned her every bit of dedication and ceremony she has received in the years following her time spent at OSU, and each memorial serves as a constant reminder to all of OSU that equality is something that needs to be fought for each and every day. Civil rights at OSU is not simply a past issue, but an ongoing movement to change the very foundation and ideals that this university was built upon.

Works Cited

Earl, Anthony S., et al. “Colleges of Agriculture at the Land Grant Universities: A Profile.” National Academies Press: OpenBook, National Academy of Sciences, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/4980/chapter/2.

Gill, Jerry Leon. “Oral History Interview with Nancy Randolph Davis.” OKSTATE Library Digital Collections, 19 Feb. 2009, https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ostate/id/8227.

Hubbell, John T. “The Desegregation of the University of Oklahoma, 1946-1950.” The Journal of Negro History, 1972, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2716982?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Kellogg, Peter J. “Civil Rights Conciousness in the 1940s.” The Historian, 1979, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24445286?seq=9#metadata_info_tab_contents.

“Langston University.” Data USA, https://datausa.io/profile/university/langston-university.

Lynch, Hollis. “The Civil Rights Movement.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia

Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/African-American/The-civil-rightsmovement.

“Nancy Randolph Davis – Oklahoma State University.” Nancy Randolph Davis | Oklahoma State University, College of Education and Human Sciences, 2 Oct. 2020, https://education.okstate.edu/about/nancy-randolph-davis.html.

“Oklahoma State University Bestows Additional Honors on Its First Black Student.” Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 2020, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2461661597/fulltext/915CC5D9319640B0PQ/13?accountid =4117.

Onion, Amanda, et al. “Jim Crow Laws.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 28 Feb. 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws.

“OSU Regents to Vote on Un-Naming Murray Hall – Oklahoma State University.” Edited by

Monica Roberts, OSU Regents to Vote on Un-Naming Murray Hall | Oklahoma State University, 17 June 2020, https://news.okstate.edu/articles/communications/2020/osu-regents-to-vote-on-unnaming-murray-hall.html.

Pollard, Gloria J. Unforgotten Trailblazer: Nancy O. Randolph Davis. The Chronicles of Oklahoma, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/chroniclesok/COO90-4Pollard.pdf .

“Two OSU Buildings Renamed to Honor Civil Rights Pioneer.” Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma State University Headlines News and Media, 23 Oct. 2020, https://news.okstate.edu/articles/communications/2020/two-osu-buildings-renamed-to-honor-civil-rights-pioneer.html.

Waldrop, Sheri. “Sapulpa Native Nancy Randolph Davis Educational Pioneer and Trailblazer.”

Sapulpa Times, 17 Jan. 2022, https://sapulpatimes.com/sapulpa-native-nancy-randolph-davis-educational-pioneer-and-trailblazer/.