By Nathaniel May

A vast expanse, flourishing with game and fowl, fruitful hills rolling atop one another with even rows of a farmer’s yield; this is the scene that has been set for man across the countryside for thousands of years. This is the family farm. As a proud descendent of men and women who have worked the Earth, as well as having familial ties to the State of Oklahoma, I have chosen to research the “Oklahoma Centennial Farm Families Oral History Project,” conducted at Oklahoma State University. Through this research I have definitely had an interesting experience navigating through hundreds of lines of interviews and looking through dozens upon dozens of stories. This is my experience.

Being the non-controversial person that I am, I scanned through the different list of archives presented by Oklahoma State and this one, seeming to be noncontroversial and not too overwhelming, caught my eye. Not only did it have the allure of appealing to all audiences, no matter the background or political ideology, it also had a very strong familiarity factor for me. I come from a family of farmers who have toiled the land for generations both here in Oklahoma and back in Germany where we originate. Not only did I have the farming lineage going for me, but my family still does have an active farm right here in Stillwater, Oklahoma. Its name is the “Friedemann Family Farm,” according to the Daily Oklahoman and Oklahoma State University. It has made appearances on both platforms and lays in a different archive within Edmond Low Library. To me it is affectionately known as ‘The Farm.’ Between The Farm and my lineage it was an easy and obvious choice for me, or so I thought.

The “Oklahoma Centennial Farm Families Oral History Project,” a mouthful to say, is an online archive designed to inform inquirers on the rich history of one-hundred-year-old plus family farms within Oklahoma. It was created and continually curated by the Oral History Department within Edmond Low Library and financed by the Roy and Marian Holleman Foundation. The archive struck great interest in me initially, giving me a lot of joy because of its closeness to my family history. It is filled with hundreds of interviews of current owners of family farms in a written format. After reading a few of these interviews I realized how close my family’s story was to that of most of the people being interviewed. After this epiphany, I set myself on a mission to get my family added to the archive. The criteria were simple and was comprised of two steps. Step one, the farm had to be at least one hundred years old; check. Step two, there had to be active production on the farm for it to be eligible for consideration; check. My family bought the farm in 1903 and is still actively producing wheat off of its 165 acres. Meeting these two requirements, I made my way down to the Oral History Department in the Edmond Low Library. I told the secretary who I was and what I wanted to do and was immediately ushered into the curator’s office. I sat there with a woman, Sarah Milligan, head curator of the Centennial Farms Archive, and we discussed my family in depth for half an hour. I had brought up the fact that Oklahoma State, the Daily Oklahoman, and my family had conducted interviews, in video format (important to keep in mind), with my great grandparents in regard to growing up on ‘The Farm’ and she politely asked if I could share them with her and I did. She told me she would get back to me in regard to my family’s eligibility, which she failed to do.

After not hearing back from the archivist I began to see things for how they were within the archive. This archive became the theoretical ‘cool kid group’ for me; once I didn’t have entry, I saw the archive for what it was. It began to take a new form: a bland, synonymous, and laborious form. Each case is a written interview which takes a fair amount of time to read through, along with the fact that a large majority of the interviews were done by the same people with the same questionairre After reading through hundreds of lines of the same information, I wanted pictures, I wanted videos, I wanted audio, which was few and far between; this simultaneously fueled my fire due to the fact that my family has all three. The reason I was so impassioned over this is because I know the importance of the family farm, what it represents for the world and especially what it represents for Oklahoma.

One key aspect of the archive that grabbed my attention the most was the format of the interview and how it was conducted. I had mentioned earlier a kind of ‘questionnaire’ that each interview contained. As I was delving deeper and deeper into the archives I was able to get a firm grasp of what was a part of the questionnaire by comparing multiple individual interviews and finding similarities in the questions they asked. The format of questioning is as follows,

- How did this land come to be in your family?

- What was the name of your farm?

- How many acres does your farm contain?

This questionnaire limits the response of the farmers being interviewed by funneling the farmers’ personal stories down into individualized blocks of information, leaving sparse room for the farmer to give the story of their farm in the way they want it to be perceived. Who is a grad student working at OSU to try and manage the life of experiences of ninety-year-old farmers into a couple of pointed questions? These interviews should be about letting the farmer tell their story freely and without interruption: to let the interview be for the farmer, by the farmer, and not for the statisticians. Stories of life on the farm cannot be categorized into a couple of facts and numeric values; where these stories thrive is in the uninterrupted accounts of the men and women of the land named Oklahoma. The accounts given by these people make Oklahoma the land it is today. Luckily, there are a few stories where enough of the farmers’ points of view can be pristinely seen despite the questionnaire.

There are hundreds of farmers to choose from but I eventually settled on wanting to portray the accounts of a man named Wayne Speer. Wayne grew up in Noble County, Oklahoma on his family farm where he lived an ideal lifestyle very typical of 20th century middle America. His accounts of daily life and mischief on the farm are what rural America and Oklahoma were based upon. His daily chores are as follows,

Well, we had to tend to them chickens, feeding chickens and watering them and gathering eggs and milking cows and feeding. We separated the milk, and they’d sell the cream. We’d use the skim milk to feed the calves and pigs and farm animals that way.

Wayne also gave accounts of his mischief when he explained how “the teacher caught three of us boys smoking out at the outhouse”. Despite his mischief, Wayne went on to serve in WWII in the Army. It is the lighthearted life stories of hardworking, loyal, ‘good ol’ boys’ like Wayne that make up Oklahoma. It is the good nature of farm life that made the people of Oklahoma who they are. It is this good nature and lifestyle that have come under attack and that could possibly be extinguished without the presence of the family farm.

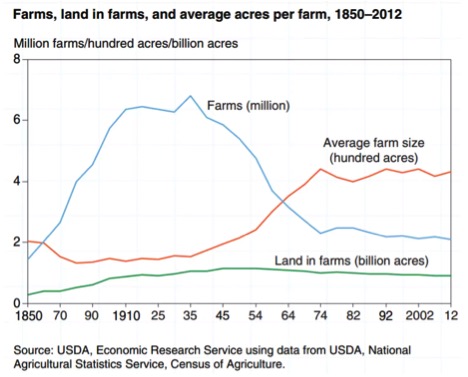

The family farm for the world represents an ancient, waning way of life. For thousands of years the Earth was riddled with family farms all the way from the fertile crescent to feudal Europe. This way of life was continually improved upon, continually enhanced, and continually passed down from generation to generation. As humans began to advance our technology, this way of life for the majority of the world is on a steep decline, without correct and adequate recording mankind will cease to remember what we did for the majority of our existence. Not only is this important and applicable on a world view, but at the view of Oklahoma as well. Oklahoma is defined by farming. These farms predate the state and they are the fabric on which it’s culture and values were derived. To document a whole culture in the same format, in the same way, and by the same people is to do injustice to not only farming culture around the world, but to do injustice to Oklahoma’s culture and history.

Although this archive has failed to inform readers and inquirers on a diverse and interesting level, it has succeeding in documenting the life of the family farm at an important crossroads. The interviews begin in 2008, a year of economic turmoil for the world but a year on death’s doorstep for the family farm. As the years have rolled on and commercial farming has gained more and more clout and efficiency, it has led to the discouragement and downfall of thousands of family farms throughout the Midwest, and more specifically, Oklahoma. With the introduction of GMOs and corporate lawyers coming into rural America, many farming families have packed up their bags, sold their combine and cattle, and left the lifestyle that has sustained their families for generations. Not only this, but in a society that continually grows wearier and wearier of hard labor and low pay, farming has been on the decline. My family itself almost gave in to the pressures that farming presents. In 1930, the midst of the great depression and the beginning of the dust bowl, my family was on the brink of selling the farm and moving to the city; thankfully investors in the Stillwater area bought the mineral rights so that we could continue our way of life (unfortunately for us we hit oil on the property in 2013). This is just one example of the how farmers might come to a profession change, yet in this changing, 21st century world, it has become exponentially more common.

The goal of this project is to “[provide] a venue for increasing awareness of the importance of farms in Oklahoma by collecting, preserving, and making information about them accessible to scholars, researchers, and other interested persons”. As one may have already guessed, I agree with this statement to an extent. Although the archive has innumerable amounts of data, it is presented in such a way that the reader is likely to die of boredom before finishing the first interview. The interviews are rich with content and history, if the interviewers were to do a video interview or present more audio along with it, the reader or scholar would be much more likely to gain interest because of the added dimensions of sight and sound. Without either of these aspects, the interview is lost in a white background. I feel like the textual medium of this archive works against itself in a way. Part of what makes farming culture in Oklahoma so important and unique to the region is the people. Seeing their weathered faces, hearing the regional accents, examining their mannerisms. This is what makes farmers who they are, their personalities, their hospitality, their witty jokes. All of this is lost when just put onto paper.

Even though this archive fails to excite readers and inquirers, it still has an important place amongst Oklahoma history. The information within its bland screens holds true and is quintessential farming history. From the accounts of what they raised, to how they bought the land, to the tragedies that struck the farms years ago. All of it is documented and readily available within this archive. Even though through a boring format, this archive succeeds in documenting these cases before they fade from this Earth.

Fall 2017